Nervous System Regulation Resources

Bringing Safety to the Nervous System [for Trauma and/or Anxiety]:

See this video for Somatic Experiencing ® self-touch exercise to calm the nervous system.

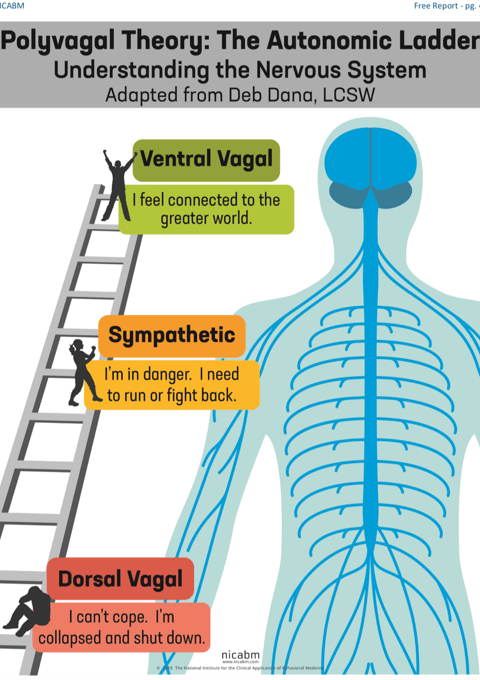

Polyvagal Theory

Somatic Regulation

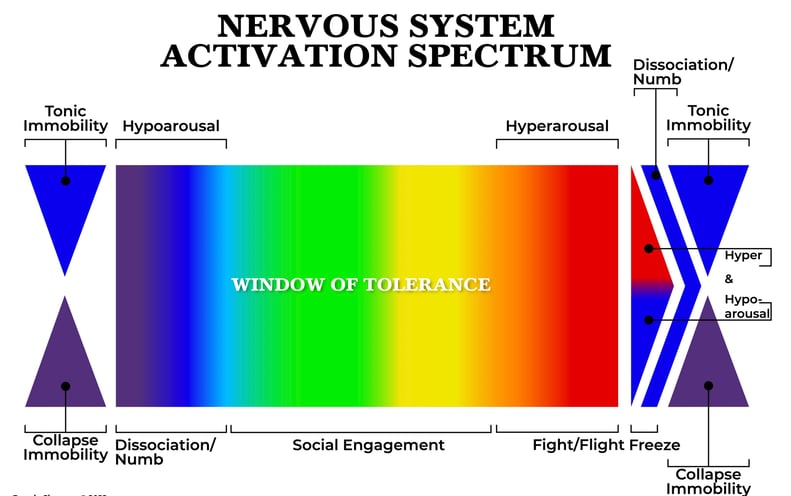

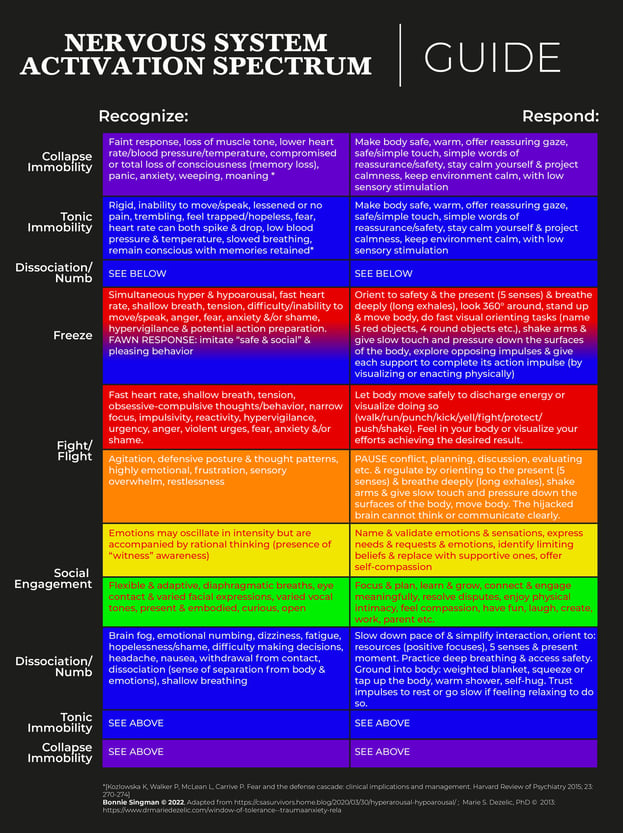

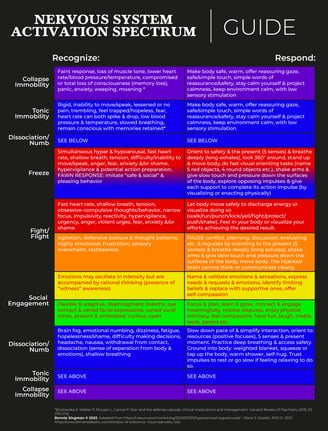

I created a Nervous System Activation Spectrum to help assess where your nervous system activation is, and its companion Guide [see below] which offers clear ways to effectively respond to your needs, emotions, and body’s signals in each state. The color spectrum makes it easy to match inner states and feelings with levels of arousal.

When our nervous system state changes, our capacity to respond changes. Wouldn’t it be helpful to know where your own or others’ nervous system activation level is, so you can respond appropriately, and stop asking of yourself or others what is impossible to give when our nervous systems aren’t on board? Useful for learning to attune to yourself and regulate your nervous system and emotions, as well as for using with clients, colleagues, couples, families, children, and anyone who communicates!:

[To learn more about the theory behind this, scroll down to the bottom of this page.]

To purchase both images as a foam board poster or framed poster GO TO: Zazzle [cheaper framing & foam board mounting option (including a double sided option with the spectrum on one side and guide on the other!)]

To purchase both images as a poster, photographic print, card, stickers, or magnet, GO TO: Redbubble [cheaper shipping]

To purchase downloadable versions GO TO:

Nervous System Activation Spectrum:

https://marvelous-experimenter-8565.ck.page/products/nervous-system-activation-sp

Nervous System Activation Spectrum Guide: https://marvelous-experimenter-8565.ck.page/products/nervous-system-activation-s-

Please share this with anyone you think might benefit (teachers, parents, therapists, and communicators of all kinds!)

Theory Behind The Nervous System Activation Spectrum

On the Nervous System Activation Spectrum, it reflects the felt experience: that we can be in our Window of Tolerance* (which means the optimal zone of arousal where we can function effectively, respond appropriately, and regulate our emotions), and then become dysregulated in either direction, feeling either increased sympathetic nervous system activation (hyperarousal) or feeling increased parasympathetic activation (hypoarousal).

While the research tells us that hypoarousal occurs after hyperarousal becomes overwhelming, and we “shut down” to protect ourselves from that overwhelm (or to enact final defense strategies), the felt experience for many of us is often that we suddenly find ourselves moving from our Window of Tolerance (or Social Engagement) right into hypoarousal (numbness, dissociation, feeling spacey, less present, unemotional, foggy etc.). This may be due to habitual patterns of overwhelm, making it so that our nervous system does not permit us to feel the “hyperarousal” that is occurring before immediately cutting off that activation with hypoarousal, to conserve energy or try to protect us in some way that was adaptive at a time in our past.

For this reason the Nervous System Activation Spectrum shows the option to move from the Window of Tolerance into hypoarousal on the left, or to first move through Fight/Flight and Freeze (defined as a mixed state of both sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activation), to then go into the hypoaroused states (after exhausting the sympathetic defensive responses), of either Tonic Immobility* or Collapse Immobility* pictured on the far right with blue and purple arrows.

Both these forms of immobility occur through the dorsal vagal branch of the nervous system* and can occur when an individual has exhausted all other lines of defense or instinctually assesses that other attempts at fighting or fleeing would be ineffective. Both involve deactivation of the sympathetic nervous system, and parasympathetic activation, include the lowering of the heart rate to below normal. Which immobility response an individual goes into is likely determined by variations in each person’s physiology.*

When safety is restored and someone is beginning to come out of these last defense immobility stages, or even when someone is exiting other dorsal vagal freeze states (even if they are not as intense) they will typically move through sympathetic activation stages [of fight/flight/freeze (simultaneous sympathetic and parasympathetic activation)] as they begin to discharge their contained life force energy, to return to regulation.* This may include emotional release/expression as well as movement impulses and energy shifts in the body.

*1: Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. New York: Guilford Press.

*2: Tonic immobility in humans appears to present as a

loss of the ability to move or call out and is thought to occur

when a person is in imminent or actual (and great) danger,

when a threshold of sympathetic arousal has been reached,

but when escape or winning a fight is not possible or is perceived

as not possible. Victims describe subjective experiences

of fear, immobility, coldness, numbness and analgesia, uncontrollable

shaking, eye closure, and dissociation (derealization

and depersonalization), as well as a sense of entrapment,

Inescapability, futility, or hopelessness. What is

(presumably) different is that human victims also typically

retain a vivid memory of the event.

(Kozlowska, Walker, McLean, Carrive, 2015, p. 273)

*3: In collapse immobility, hypoxia (lack of sufficient oxygen to the tissues) occurs, disrupting signals to maintain muscle tone, and effecting consciousness “ranging from compromised consciousness to a complete loss of consciousness (syncope). In some individuals cerebral hypoxia can compromise inhibitory control and manifest as increased anxiety, panic, weeping, or moaning” (Kozlowska, Walker, McLean, Carrive, 2015, p. 274).

*4: Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. New York: W.W. Norton.

*5: Kozlowska K, Walker P, McLean L, Carrive P. Fear and the defense cascade: clinical implications and management. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 2015; 23: 270-274

*6: Levine, P. A., & Mate, G. (2010). In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness (1st ed.). North Atlantic Books (p.90-91).

Contacts

lightsomatic@gmail.com

619-289-7604

Bonnie Singman, MA, LPC, PSEP